Four others perished in a rescue 60 years before Lee grounding

Old Colony Memorial and Plymouth Rock front-page masthead, with “Sad Catastrophe” headline over the story of the tragedy. April 19, 1867. Click for larger version.

By Scott B. Anderson

Sixty one years before the Lee tragedy, four other Manomet men lost their lives while trying to save the crew from a schooner that grounded offshore.

Cromwell F. Holmes (my great-great-great-uncle); Amasa Bartlett Jr.; (my fourth cousin, five generations removed); James H. Lynch; and his son, James, drowned during the attempted rescue of the crew from the schooner Charles H. Moller, which grounded during a gale on Wednesday, April 17, 1867.

All told, six “noble-hearted young men [were] sacrificed as victims” of the storm — the other two died in incidents unrelated to the Moller, according to a story a few days after the storm in the Old Colony Memorial and Plymouth Rock. (Read the OCM story from a few days after the tragedy. Read a version picked up by the Sacramento Union the next month. And a very thorough history of the Moller tragedy by Hanson historian Mary Blauss Edwards.

I am told that Jack, a history buff who has spent summers in White Horse since he was a child, wonders why there is no memorial to these four heroes; we agree. There should be.

The Moller was heavily laden and went aground “some distance from shore outside the breakers” and was “lying in a heavy sea with stern and upper works breaking up,” the Old Colony story reported, noting that “great fears were entertained for the safety of the crew.”

The members of Manomet’s volunteer lifesaving crew jumped into their lifeboat and headed out to save the Moller’s crew. Aboard the lifeboat were the four who were to later perish, along with Otis Carver, John Briggs, William Jordan and McDonald Nickerson. They rowed through the rough surf and tied a line to the schooner. But suddenly, “a heavy sea overturned the boat,” the OCM said, and “all except Briggs were thrown into the water.” The boat righted, and Nickerson, Carver and Jordan climbed back in with Briggs. Bartlett, Holmes and the two Lynches “perished in sight of their parents and houses and near the vessel whose helpless crew they had so nobly resolved to rescue.”

Their bodies were recovered the next morning.

The crew was rescued the next day, thanks in part to Allen Mellencourt, who tried to reach the schooner in a dory by himself, but lost an oar enroute and had to make his way back to shore with only one. He returned “with others, and brought the crew safely to land.”

The OCM story includes a very moving passage that pays tribute to the four who died:

“Possibly for one’s own flesh and blood a man will lay down his life; but he who nobly braves the wild maddened sea in obedience to a sacred sympathy for the helpless stranger, daring and losing all, bears a soul indeed heroic and worthy of highest honor. Lives so offered up are holiest teachings. Such examplars challenge sacred emulation and elevate a generation in true nobility.”

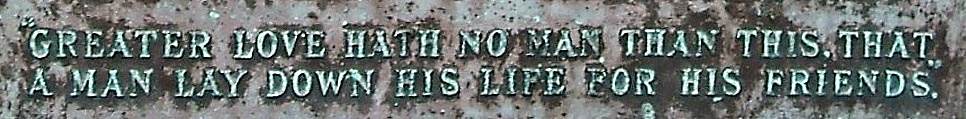

While there is an extraordinarily well-deserved memorial at Manomet Point to the brave coast guardsmen who perished while trying to help the Robert E. Lee, one wonders why there is no memorial to those who died 60 years earlier in very much similar circumstances. There should be.

Cromwell F. Holmes was my great-grandmother Elizabeth Holmes Anderson’s uncle. They were part of a sprawling family that has lived in Manomet since the 1600s, with vast farmland at Stage and Manomet points. My connection to Amasa Bartlett Jr. is through my paternal grandmother, Eudora Stewart Bartlett Anderson. The Bartlett family in Plymouth goes back go the 1620s — Robert Bartlett arrive on the Anne in 1623 and married the daughter of Mayflower passenger Richard Warren — and is among the founding families of Manomet.

There was “sorrow and gloom” beyond the Moller that stormy day. Henry Hunt and George Lane also drowned during the gale and its aftermath. Both were aboard the schooner Willie Lincoln off the Gurnet. Hunt and a crew mate were trying to repair damage on the schooner when Hunt was “swept helpless into the ocean. . . Hunt struggled long and nobly, but all went against him.”

Two shipmates set out in a dory to rescue Hunt. Unable to save him, they set out for safety at Plymouth Beach a mile away, but the boat was swamped as it neared shore and George Lane was swept away and drowned.